Trinitrophenol, better known as picric acid, carries a fascinating past. In the mid-1800s, chemists in Europe found this yellow compound during ambitious experiments that changed the face of both dyes and explosives. At first, cloth makers prized it for its vibrant yellow hue. By the late 19th century, trinitrophenol took on a new reputation as militaries around the world stole a page from its explosive power. Some may recall stories from World War I, when artillery shells packed with this chemical spelled devastation. This crossover from textiles to munitions stands as a reminder of science’s double-edged sword. Trinitrophenol sits at a crossroads in history, raising tough questions about progress and responsibility. Those stories from the trenches—the shell shock, the injuries, the burst artillery—these link back to picric acid as an unwilling character in humanity’s ongoing experiment with chemistry.

Picric acid is a pale-yellow, crystalline solid. It doesn’t blend in quietly, whether kept in a lab shelf or handled in a munitions factory. Chemists recognize its sharp, acidic bite. The smell carries a lingering odor, something a bit medical, a bit industrial. Factories once stored barrels labeled with big black warning signs, alerting workers of the contents’ hazards. Today, trinitrophenol finds application far from the battlefield. In laboratories, it takes part in the manufacture of dyes, medicines, and antiseptics. Its use in munitions has declined, with safer alternatives now in rotation. The shift says a lot about evolving priorities: worker safety, environmental health, and a careful respect for chemistry’s raw power.

Any chemist worth their salt will tell you, picric acid doesn't tolerate rough handling. It crystallizes in bright yellow, needle-like structures. Trinitrophenol melts at 122.5°C and won’t dissolve in water quite as well as nitroglycerin, but it mixes with ethanol with little trouble. The density—about 1.7 g/cm³—gives it some heft as a powder. More importantly, it’s both a strong acid and a powerful oxidizer. Careless storage lets it react with metals to form picrate salts. These compounds look harmless but explode at the drop of a hat, for example, if a metal cap on a bottle collects dry crystals. Even vibrations or friction can kick off an accident. This risk follows trinitrophenol at every step—from synthesis to disposal. My own experiences in academic laboratories taught me to treat every glass vial like a loaded weapon when chemicals like picric acid were in play.

You’ll spot trinitrophenol by its unmistakable color and hazard labels: UN 0154, classed as a high-explosive, toxicity warning, and corrosive symbol. Producers list a purity of 99% or better for technical and analytical use. Standard packaging includes wetting with at least 10% water, a critical precaution that helps dampen its explosive nature. The label must state the net weight (minus water), batch number, handling instructions, and the chemical’s unique registry number (CAS 88-89-1). Technical data sheets explain melting point, solubility figures, and risk phrases such as “explosive when dry,” “toxic by inhalation or ingestion,” and “dangerous to the environment.” You can’t ignore the label, not just for compliance, but to remind everyone that this isn’t a compound to take lightly.

Chemists prepare trinitrophenol by nitrating phenol using concentrated nitric and sulfuric acids. The technique calls for patience and caution. A flask of cold phenol meets carefully chilled nitric acid, all under stirring. Sulfuric acid acts as the catalyst, keeping the reaction moving forward while soaking up extra water. The process generates heat; cooling is vital—nobody wants an incident in a crowded laboratory. One slip, and you’re left with hazardous fumes and a risk of detonation. Post-reaction, the product crystallizes out, collected and repeatedly washed to remove acidic residues. Later, each batch sees careful neutralization with sodium carbonate before the crystals end up wet-packed for transport. It’s a dance between risk and reward, with experience counting more than any textbook ever could.

Trinitrophenol reacts with a broad range of substances. Alkaline materials prompt it to form soluble picrates, which in turn can be even more sensitive to shock or friction than picric acid itself. Mix with lead, copper, or iron, and you create metallic picrates. These salts brought more than a few factory explosions in the last century, pushing the industry to switch to plastic or glass containers. Picric acid also participates in condensation and substitution reactions that make it valuable for chemical synthesis. Organic chemists sometimes tweak its structure to produce dyes, drugs, or analytical reagents. Yet, every modification demands its own safety protocols, and every new derivative needs toxicity evaluation from scratch.

Across industries and languages, trinitrophenol travels under many names. Picric acid, Melinit, Phenoltrinitrate, Lyddite (in the context of explosives), and sometimes as 2,4,6-trinitrophenol. Each tag ties back to a different historical use: Melinit for German munitions, Lyddite for British shells. Commercial suppliers may use these names interchangeably, but those working in pharmaceuticals or dye manufacture still know it first and foremost as picric acid. Anyone handling the product should check the label, as the explosion risks don’t care about what you call the yellow powder inside.

Handling picric acid takes grit and discipline. Safety standards require that trinitrophenol always stays moist—above 10% water content—because dry crystals present a constant explosion hazard. Workers don gloves, goggles, and sometimes even face shields. Laboratories limit the total volume stored on site. Local fire marshals keep a close eye on records. In my university lab, every container carried bright red tape marking its fill date and the last check for water content. Any old samples or dried residue warranted immediate disposal under trained supervision. Equipment made from copper, lead, or other reactive metals stays out of the picture, replaced by glass or plastic. Strict ventilation keeps fumes from pooling, especially when reactions run hot. Emergency protocols drill staff for spills, leaks, or—worse still—any sign of crystallization on metal lids. Nothing sharpens focus like running a reaction with picric acid in a crowded teaching lab.

Picric acid once sat at the center of military explosives, coloring artillery shells and even aerial bombs. These days, its story doesn’t end on the battlefield. In manufacturing, chemists use it to make dyes, particularly in yellow and orange hues for textiles. Medical researchers turn to trinitrophenol to create antiseptics and even some drugs, leveraging its strong antibacterial effect. Histologists employ it as a tissue stain, revealing secret details under the microscope. Analytical chemists count on its ability to test for the presence of metals or certain alkaloids. Each use brings its own set of protocols, but the shadow of explosion risk never disappears. As chemistry pushes new boundaries, the chemical’s role shrinks, with safer molecules taking its place where possible.

Research into picric acid continues, even as industry moves toward safer reagents. Synthetic chemists explore trinitrophenol derivatives for new pharmaceuticals, always weighing the therapeutic benefits against toxicity and handling risks. Scientists study the molecule’s interactions with proteins and metals, hunting for insights that could improve diagnostic kits. Environmental engineers investigate methods for breaking down picric acid waste, mindful of both worker safety and river ecosystems. Any project involving the chemical starts with a full risk assessment—a fact my industry contacts repeat often when discussing their work. The conversation never loses sight of past accidents, and regulations keep research honest and careful. Universities spend as much time teaching safe handling as synthetic routes, recognizing that every batch of trinitrophenol presents both opportunity and challenge.

Picric acid’s toxicity is hard to brush aside. It can damage skin and mucous membranes, irritate eyes, and cause chemical burns. Inhalation brings headaches, dizziness, and in some cases, more severe effects. Skin contact may result in yellow stains and even ulcers if left untreated. Chronic exposure poses risks to the liver and kidneys, tying back to the body’s tough time metabolizing nitro compounds. Historical case studies tell hard tales of factory workers developing anemia or systemic damage after repeated exposure. Studies in laboratory animals confirm these hazards. Handling spills or wastes isn’t just a regulatory box ticking exercise; it’s a matter of worker protection. As chemists look for safer alternatives, every new reagent is measured against the harm done by trinitrophenol. Toxicity studies set the bar for what gets to stay in a modern laboratory.

Picric acid’s golden age has passed, but it still holds a niche in research and industry. Modern explosives seldom rely on it, yet the compound shows up in specialty reagents and stains. Emergent chemicals outshine it on the safety front, reducing both risk and environmental impact. Researchers stay motivated by regulatory pressure and an eye to sustainability, drafting out greener synthesis routes and safer analogs. Waste treatment technologies continue to evolve, inching closer to a chemistry portfolio without the long-term baggage of legacy compounds. Based on years working alongside regulatory compliance officers and green chemistry advocates, the direction is clear: future laboratories will remember trinitrophenol as a marker of both ingenuity and the growing pains of chemical safety. The lessons learned keep shaping new generations of scientists tasked with choosing progress, but never at the expense of well-being or caution.

Trinitrophenol pulls up two images in most folks’ minds: chemistry class and powerful explosives. Known by most as picric acid, this yellow crystalline solid packs a punch. Long before modern explosives like TNT, militaries and miners relied on trinitrophenol’s energetic nature. The stuff can go off with enough force to rip apart stone, making it a choice pick for blasting rock or loading up early artillery shells. Soldiers suffered for it, though—trinitrophenol sometimes corroded shells, making them unpredictable. No one wants to handle materials with a mind of their own, especially in a war zone.

Before folks fully grasped its risks, trinitrophenol showed up in medicine cabinets. Doctors used diluted forms to treat burns and wounds, betting on its germ-killing effect. Early days of medicine leaned on what was available. Back then, people took their chances because better options didn't exist yet. Sometimes wounds healed. Sometimes folks ended up with nasty complications. Medicine chased after safer ways, and soon trinitrophenol faded out of the pharmacy.

Any knitter or dyer in the late 1800s knew that trinitrophenol left behind a bold yellow stain. Textile makers jumped at the chance to create vivid colors, especially when natural dyes came up short or cost too much. That said, the color stuck—a lot. Hands, clothes, wood floors—everything yellowed. The chemical soaked its way into the fabric and the process, stamping out gentler alternatives until health concerns turned the tide.

In research labs, trinitrophenol still pulls its weight. Chemists use it to test for the presence of certain metals or amino acids thanks to its sharp reactions. In my college days, professors pointed to its crystal structure to explain how different chemicals interact. Teachers liked to mention it since it grabs attention. But even here, its dangers loom. Researchers handle tiny samples under heavy safety rules—masks, gloves, exhaust fans—because nobody wants to see how explosive it can get.

Industry keeps trinitrophenol on a tight leash. Regulatory agencies like OSHA and the EPA insist on careful handling and strict storage rules. Factories log every ounce and follow emergency plans. Mixing it with other chemicals ramps up the risk, so companies favor smarter controls and swap trinitrophenol out for safer options whenever possible. No one wants a workplace accident traced back to a shortcut.

The story of trinitrophenol is a warning. Strong chemicals earn respect for a reason. Today, safer explosives have replaced much of trinitrophenol’s former glory in mining and the military. Modern medicine relies on gentler antiseptics, and textile makers turn to dyes far less harmful to workers and the environment. Still, complete substitutes don’t exist for some specialized uses. So, the real solution comes down to careful oversight and constant education. People do make mistakes, but training, and practical respect for what these chemicals can do, keep disaster at bay.

Looking back, I remember chemistry lab days where instructors reminded us that even a little bit of carelessness could ruin things for everyone. The lesson rings true in chemical plants, research labs, and policy meetings. So, trinitrophenol sticks around, not just as a compound but as a lesson in balancing power with caution.

Trinitrophenol, or picric acid, has earned a reputation that sounds straight out of a movie. Old bomb squads, chemistry teachers, even military historians know this yellow powder as a substance that can blow up if treated wrong. My own brush with it came during a college organic chemistry lab. The instructor drilled in the warnings: dry picric acid explodes if you drop the bottle, while the wet kind stays much more stable.

Let’s clear up one thing. Picric acid doesn’t explode just because someone looks at it sideways. Danger doesn’t lurk in every bottle: the risk grows when the substance dries out. In that state, a hard knock, scratch of metal, or heat source can trigger a detonation. In contrast, storing it damp, usually around 30% water, keeps it relatively tame.

Picric acid saw action in the trenches of World War I, filling artillery shells and grenades. Back then, factories hummed with production. These days, the chemical has taken on a quieter role— found in some labs, used to dye textiles, test proteins in urine, or act as a reagent in chemical reactions. It lost some appeal as a military explosive because other compounds offer greater power and easier handling.

Still, news trickles out every so often about a forgotten container left high and dry on a shelf, discovered during a school or hospital cleaning spree. Emergency crews then show up, suited for worst-case scenarios, to safely dispose of the stuff. Those headlines aren’t hype: dry picric acid can explode with friction or impact. Over the years, I’ve met chemistry teachers who stumbled on 40-year-old samples, untouched and yellow, just waiting for trouble.

My chemistry professor insisted on respect for picric acid, but not fear. He treated his small supply as a tool, not a ticking bomb. He kept it wetted, stored it in a cool place, labeled it with two layers of warning tape, and logged every use in a notebook. He showed that the difference between an accident and a safe lab comes down to care and process, not luck. His approach lines up with what experienced chemists and safety officers recommend. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institutes of Health both emphasize moisture. If the acid dries out, treat it as a potential explosive, call hazardous materials professionals, and never try to re-wet it yourself.

Respect matters more than panic. Storing trinitrophenol wet, keeping it away from metal containers, and disposing of aging supply lowers the risks. People who run labs or manage old building inventories should check for old bottles, learn the protocols, and connect with hazardous waste experts if needed. Training staff and writing clear safety guides also serve as good lines of defense. Even in schools—where teachers swap classrooms and supplies turn up in back closets—a system that tracks chemicals pays off.

Picric acid’s dangers come down to knowledge, routine checks, and the willingness to ask for help if something feels off. While its story has some dark chapters, most accidents start with poor storage or forgotten lessons on chemical care. If people treat trinitrophenol with the same caution as gasoline or fireworks, it rarely causes trouble.

Trinitrophenol, also called picric acid, reminds me of those old chemistry stories where the tiniest mistake led to disaster. Its yellow crystals might not look threatening, but don’t let appearances fool you—this compound can explode if treated carelessly. Even today, in labs and factories, there’s tension in the air when someone brings out a jar of the stuff.

Just a few grams of dry trinitrophenol can cause serious damage if mishandled. Explosions aren’t just the stuff of old war movies—they happen when folks get too casual. I’ve watched seasoned scientists always check containers for moisture. Keeping the compound damp keeps it from turning sensitive to bumps and friction. Risking it dry just isn’t worth the consequences.

No amount of know-how can swap out for gloves and goggles. This chemical burns skin and eyes. Nobody wants to remember an experiment by the scars left behind. I’ve worn splash goggles that wrap around the side of my face, not the regular safety glasses that always seem to find an excuse not to fit. Full-length lab coats and double gloves—no one laughs about being overdressed when working with hazardous compounds. The importance of changeable gloves became clear the first time a drop slipped past a thin pair.

Trinitrophenol’s fumes can irritate the lungs. I once watched a colleague cough for an hour after a careless fume hood setup. Today, I won’t even open a bottle if there’s a question about airflow. Proper hoods turn a risky job into something manageable. In a cramped or stuffy space, the risks feel amplified—and for good reason.

Unstable compounds don’t belong near heat, sparks, or rough handling. I check containers for rust or dry crystals forming around the lid. Sealing it tight and storing it where temperatures don’t bounce all over feels routine, but it’s how you keep that jar from becoming a news headline. I learned to avoid metal spatulas for transfer; wooden or plastic ones don’t make sparks. I label every bottle in thick, clear letters. If someone needs to ask twice what’s inside, the labeling has failed.

Trinitrophenol has a bad habit of sticking around. Flushing it down the drain or tossing a jar in the regular trash is a quick path to trouble. Chemical waste rules often get ignored for less-harmful compounds, but here, following procedure is non-negotiable. Waste bins get checked weekly, pickup logs signed carefully. I prefer working in groups so no one has to move hazardous waste alone. More eyes, less risk.

In my time around chemicals, the best safety lessons came from quiet, daily habits. Trinitrophenol deserves this level of respect because it doesn’t give second chances. Some labs hold morning talks before big operations—just five minutes to review steps and gear can prevent days, or lives, lost to a mistake. The biggest lesson from working with unpredictable chemicals is that the culture of safety only works if everyone believes it’s more important than getting done fast.

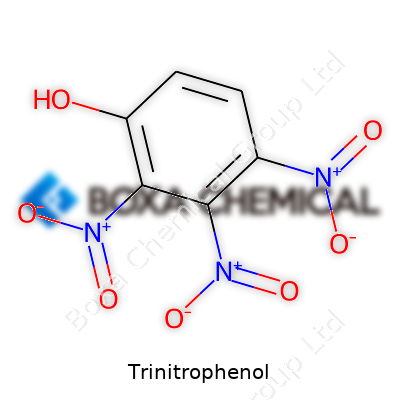

Trinitrophenol, known by most folks as picric acid, doesn’t just show up in chemistry textbooks—it’s a compound that built legacies in labs and shook up the world of explosives. Its structure sets it apart: a benzene ring at its core, loaded with three nitro groups and a single hydroxyl group. Seeing this structure on paper takes me right back to the chattering of glassware and sharp smells that once filled my college lab. Here, the change in properties just from swapping out a hydrogen for a nitro group couldn’t go unnoticed.

Three nitro groups attach to the benzene ring at the 2, 4, and 6 positions. There’s a hydroxyl group hanging at position 1. The way these pieces fit makes picric acid more acidic than plain old phenol. Swapping hydrogens with those heavy nitro groups withdraws electrons, so the molecule turns more eager to lose its proton. That sour snap—a tangible change for anyone who remembers titration lab days—shows up because of this exact arrangement.

This isn’t just some academic quirk. Back in the day, folks saw how this structure made trinitrophenol suitable for dyes and military explosives. When you see the crisp yellow crystals of picric acid, you’re staring right into chemistry’s ability to change society. Chemistry students learn pretty fast—one spill or exposure to dry air, and you discover just how unstable that molecular arrangement can get.

It’s easy to brush off chemical structures as the domain of scientists, but trinitrophenol’s structure became everyone’s business in the late 1800s. People handled it in armories and textile factories without much protection. The molecule’s three nitro groups might look unassuming in a diagram, but they’re a recipe for instability and sensitivity to shock. Accidents in munitions plants shaped laws, drove invention of safer materials, and cemented the need for chemical literacy among workers—not just the folks running the lab.

In modern labs, being careless with trinitrophenol can still lead to rough consequences. Training always drills home: always store it wet to avoid accidental detonations. Having worked with both fresh students and old-timers, I saw firsthand how a respect for molecular structure turns into life-saving habits. Think of all the progress in explosive detection, safe disposal, and chemical regulations—every bit of it ties back to knowing what that ring, those nitros, and that single hydroxyl signify.

Today, the lessons from trinitrophenol’s risks echo across chemical safety standards worldwide. Clear labeling, strict moisture controls, and safety equipment changed the way people prepare, use, and store reactive compounds. Research keeps moving toward replacements for hazardous compounds in industrial and lab work. By choosing less sensitive materials for explosives and dye production, industries cut down on injuries and environmental damage.

Teaching the structure—showing not just the bonds and groups, but what those features mean in practice—opens eyes fast. Chemical education needs to link back to real-world risks and responsibilities. It’s not enough to memorize a structure; understanding what it does, and how to handle it, makes that knowledge powerful.

Picric acid’s chemical structure packs a story about chemistry’s influence outside the beakers: from war zones to factory floors and into safety textbooks. Whenever we look at a complex molecule, the bonds and groups need to mean something outside the page. That’s how the knowledge sticks, and how the next generation learns not just to draw a molecule, but to respect its risks and possibilities.

Trinitrophenol, better known as picric acid, carries a heavy reputation among chemists — and anyone who has worked even briefly with explosives or old reagent cabinets knows why. With this compound, stories float around labs about ancient bottles drying out and turning into a dangerous crystal-crusted nightmare. Ignoring the rules with this material often ends badly; a quick search in chemical safety databases reveals just how many schools and industries have faced building evacuations or legal fines for doing storage wrong.

Plastic won't do the job. Trinitrophenol reacts with metals, creating even more sensitive substances that have caused accidental detonations in unlucky workshops. Using glass containers fitted with tight, interference-resistant lids stops external contamination and limits the chance of leaks. What goes in with the chemical matters, too. Adding a bit of water — not too much, not too little — controls the risk. Picric acid with moisture (above 30%) stays far less shock-sensitive, so those old bottles you sometimes spot with desiccated, flaky residue are red flags that someone got careless.

No one keeps trinitrophenol on a crowded shelf, sandwiched between other reagents. A locked, dedicated explosives cabinet, distant from sources of heat, impact, or open flame, makes all the difference. Cabinets built for flammable or explosive chemicals offer thick metal, secure latches, and signs that leave no doubt about what’s inside. This isn’t just red tape; it lines up with what national agencies recommend. OSHA in the United States cracks down on labs that skip these basic safeguards, and for good reason. A moment’s inattention during a fire drill or a frantic spill response could put someone right in harm’s way.

Labels do more than remind someone what’s inside the bottle. They should carry the date of purchase, original supplier, and water content. Stores run audits every year. If water dips below safe levels, the container gets disposed of by professional hazardous waste teams — not tossed into the trash behind the building. Several universities have already learned that delaying disposal can cost millions in emergency clean-up fees, not to mention the risk to janitors, inspectors, or anyone never told about that forgotten bottle on the back shelf.

Books cover protocol, but hands-on training drills lessons home. New staff and students need strong reminders that trinitrophenol takes a different mindset than other reagents. Keeping chemical records digital helps track every bottle. Well-practiced emergency procedures — like containing a spill, knowing who to call, keeping clear evacuation paths — make sure instinct and confidence carry workers through surprises.

Every incident with trinitrophenol tells the same story: shortcuts never pay off. Chemistry brings plenty of useful and harmless substances, but materials like this call for a responsible, realistic approach. A bit of humility goes a long way — treating storage as a community job, never a personal afterthought — and stops headlines before they start.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol |

| Other names |

Picric acid 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol Aurintricarboxylic acid |

| Pronunciation | /traɪˌnaɪtrəʊˈfiːnɒl/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 88-89-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1209222 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:22227 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1537 |

| ChemSpider | 2039 |

| DrugBank | DB06774 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.304 |

| EC Number | 207-035-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | **656** |

| KEGG | C02580 |

| MeSH | D014278 |

| PubChem CID | 6626 |

| RTECS number | SX5600000 |

| UNII | OUZQXOBPAM |

| UN number | UN0154 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4020607 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H3N3O7 |

| Molar mass | 227.13 g/mol |

| Appearance | Yellow crystals |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.76 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Moderately soluble |

| log P | 0.83 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.4 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 0.38 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.90 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -48.0·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.656 |

| Viscosity | 1.245 cP (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 3.77 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 146.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -240.1 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1223.6 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | D08AX04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Explosive, toxic, harmful if swallowed, causes severe skin burns and eye damage. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS06, GHS03, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS01 GHS02 GHS06 GHS05 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H301 + H311 + H331, H272, H302, H315, H319, H335, H373, H411, H300, H310, H330 |

| Precautionary statements | P210, P250, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P273, P280, P284, P301+P310, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P307+P311, P311, P320, P330, P370+P378, P372, P308+P313, P403+P233, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-4-3-OX |

| Flash point | 79 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 300°C |

| Explosive limits | Explosive limits: 0.9–40% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ oral (rat): 200 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 202 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | SN4550000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) of Trinitrophenol is "0.1 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 25 mg/m3 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 75 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Picramic acid Picramide Styphnic acid |