Long before anyone imagined advanced plastics in cars or high-speed trains, Leo Baekeland mixed phenol with formaldehyde and changed the world. This happened around 1907, marking one of those rare moments that shaped the twentieth century. Before this, craftsmen stuck to naturally-derived resins, watching them crack, melt, or fall apart. Baekeland’s Bakelite came along and suddenly, radios, phones, and even jewelry felt tougher, easier to shape, and ready for mass production. IBM’s early office machines used Bakelite panels. Factories began to trust this material in applications that usually failed under heat or electrical stress. The knowledge spread quickly—Russia, Germany, and Japan saw their own labs turning out phenol-formaldehyde products to accelerate their industrial growth. People today might overlook these roots, but the modern world owes a lot to that pivotal discovery in a small Yonkers lab.

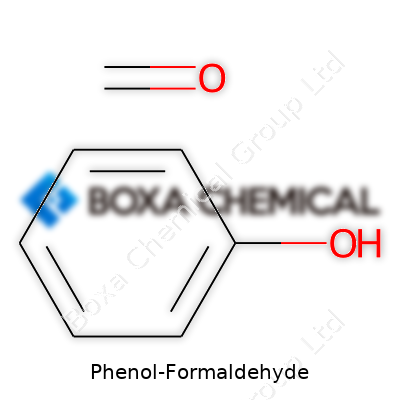

Phenol-formaldehyde resin doesn’t offer the flash of lightweight carbon fiber or eco-friendly bioplastics. Instead, people reach for it when they’re after strength, stability, and stubborn durability. The resin starts as a basic reaction product between phenol (a coal tar or crude oil derivative) and formaldehyde, giving a sticky liquid that cures to a rigid, tough solid. The most common forms include novolac and resol—each type handles its own processing challenges: novolacs demand a separate hardener, while resols can cure on their own under heat. Anyone who has ever handled electrical insulation boards, billiard balls, or brown handles of old cooking pots has probably met phenol-formaldehyde. It may look plain, but this resin is not about looks—it’s all about survival in tough conditions.

Once formed, the cured resin resists heat and chemicals in ways many plastics just can’t match. Press it into shape, apply heat, and phenol-formaldehyde hardens permanently. The resulting material shrugs off many solvents, resists water (although not completely immune to prolonged soaking), and stands firm against acids and oils. Its electrical insulating abilities give it an edge wherever sparks or surges threaten cheaper plastics. Physically, phenol-formaldehyde resists warping and flows only at high temperatures—once set, it locks in its form for good. Density ranges from about 1.3 to 1.4 g/cm³. The surface feels hard and cold, sometimes gritty, and the brown tint shows up in nearly every factory-produced version. These aren’t subtle traits—they matter when selecting materials for industrial gear that operates year after year.

Specifying phenol-formaldehyde resin means watching several numbers: free formaldehyde content, viscosity, softening point, ash content, and curing speed. Standards from ASTM and ISO offer guidance, and reputable producers often publish detailed data sheets. Customers want low free formaldehyde for workplace safety and environmental reasons, but high enough for efficient curing. Shelf life matters too, with many resols needing cool storage and fast turnover. Labels on bulk shipments flag not just grade or batch, but potential allergens and toxicity warnings. Some companies add UV stabilizers or fire retardants, sometimes listed under trade names that hide the chemistry but aim for a clear purpose—longer lifespan or safer use in public spaces.

The production process demands a careful hand to guide the exothermic reaction between phenol and formaldehyde. It typically runs in stainless steel reactors under controlled temperature and pH. Manufacturers can push the reaction with basic or acidic catalysts: acids yield novolacs with a longer shelf life, while base promotes resol formation for one-pot curing. The mix boils and thickens, spitting out water and unwanted byproducts, guided always by pressure gauges and skilled workers who know when to stop. Filters catch undissolved solids, while the crude resin gets washed or distilled to trim away excess reagents. Spray-drying or flaking turns the liquid into a powder for easier handling. Small missteps can alter performance, so tight quality controls run through every batch. My own time in chemical labs showed me firsthand: even routine runs can go off course, and a vigilant team prevents losses in both quality and safety.

Phenol-formaldehyde resin lays down a lattice of bonds tougher than many competitors. That backbone consists of aromatic rings connected by methylene bridges. Once set, it resists breaking apart, but chemists can tweak the chain with fillers or reinforcements. Common additives include wood flour, glass fiber, or graphite to boost strength or impart special conductivity. Surface modifications can add functional groups for better painting or layering in composites, letting the resin play new roles in circuit boards and friction materials. Advanced labs experiment with chemically grafting in nanoparticles or rubberized segments, giving the old workhorse a path into more extreme environments—like turbine blades or lightweight armored panels. The toolbox has only grown with computational insights and new catalysts that lower energy costs in manufacturing.

People outside chemistry circles sometimes mix up phenol-formaldehyde resin with broader terms like Bakelite, Novolak, or Resole. Bakelite stands as the historical brand that stuck, often used loosely for all phenolic resins in North America. Chemists in Europe might call similar products by company labels such as Durite or Plenco, and Asian suppliers ship “phenolic resin” powder to fit insulation and adhesive markets. Synonyms like PF-resin or PHFR show up in research literature, and commodity codes help importers trace shipments globally. Each name circles the same core chemical story, just wrapped in a new commercial package to fit local markets.

Working with phenol-formaldehyde demands respect for both volatile chemicals and byproducts that pose health risks. Formaldehyde rates as a known human carcinogen, requiring careful ventilation and protective gear during processing. Phenol can burn skin and irritate lungs, so facilities need clear access to eye washes, gloves, and emergency protocols. Finished resins off-gas less but still call for monitoring in confined spaces—particularly in schools and public buildings where old panels or tiles break down. Factory audits and regular employee training go a long way. Regulatory bodies such as OSHA, REACH, and local environmental agencies keep suppliers on their toes, setting strict thresholds for airborne emissions and wastewater discharges. Ignoring these risks leads to real costs—higher sick leave, lawsuits, and even criminal penalties. Experience has taught many that a well-run plant, with simple but rigorous procedures, never goes out of style.

Phenol-formaldehyde delivers where toughness, thermal resistance, and caught-in-the-act reliability matter. Automotive brakes and clutches take advantage of its friction performance, letting drivers stop safely under hard use. Electrical transformers and circuit boards rely on its insulation, avoiding short circuits and fire. Foundries use phenolic resins as binders for sand molds, shaping millions of engine blocks and gears every year. The construction industry opts for phenolic laminates in high-traffic surfaces—think bowling alleys, countertops, or subway walls—where impact and scuffs would ruin lesser materials. Ballistics and aerospace sectors now tap modified phenolic resins for lighter, more efficient shielding. Even artists appreciate the look and feel of old Bakelite jewelry, a retro classic that still draws collectors.

Recent research digs into lowering formaldehyde content without weakening the backbone. Universities and startups hunt for alternatives, like bio-based phenols from lignin or tannins, hoping to shrink the resin’s reliance on fossil fuels. Some teams add nanoparticles for thermal conductivity or new fire protection strategies using phosphorus compounds, moving phenol-formaldehyde out of its traditional niches. Others tinker with hyper-efficient catalysts, seeking to cut energy use and open new forms of recycling. Computers have also stepped in, running simulations to map out how structural tweaks shift heat resistance or toughness. Collaboration with sectors like aerospace and high-speed rail pushes the resin into new extremes, demanding ever-more creative chemical solutions.

Phenol-formaldehyde’s utility brings heavy baggage—formaldehyde emissions cause cancers, respiratory irritation, and allergic responses. Decades of workplace studies tell a clear story: factories with poor ventilation or outdated safety gear end up with sick workers, lawsuits, and environmental fines. Researchers track inhaled formaldehyde and skin exposures, mapping the risks for workers and end-users. Animal studies confirm chronic dangers, yet some hazards shrink as curing reactions finish. Regulators step in with strict exposure limits and product certifications, watching schools and hospitals for harmful off-gassing. Companies commit time and money to manage residues and warn customers when materials reach the end of their life. There’s no shortcut here, just a steady crawl toward safer chemistries, lower exposures, and honest reporting.

The world around us shifts away from fossil fuels and toward more sustainable, health-conscious products. Phenol-formaldehyde resin sits at a crossroads—manufacturers balance legacy uses with the push for bio-based source materials and lower-emission processing. Labs tweak formulas to cut toxicity while hunting for clean, recyclable systems that don’t lose the old material’s heat and abrasion performance. Green building standards and new auto safety rules push for verified, low-emitting phenolics or alternatives altogether. The continued evolution comes not from wishful thinking, but from gritty lab work and tight partnerships between suppliers and customers. Some makers lean into circular economy ideas, reclaiming resin waste for boards or insulation. For anyone betting on phenol-formaldehyde’s future, adaptability and courage to change will matter more than tradition.

Wander through any home improvement store and you’ll find sturdy plywood sheets stacked higher than your head. Look closer, and you’ll see the results of phenol-formaldehyde resin hard at work. This resin delivers serious mechanical bond strength, so panels keep their shape even after years of carrying weight or facing rain. Carpenters and builders count on it to hold together subfloors, furniture frames, and even the iconic kitchen countertop. Heat and moisture can ruin inferior adhesives, but this resin keeps its grip. Without it, the building trades would likely face more costly repairs and warping nightmares.

Industrial workers and engineers don’t often have the luxury of easy conditions. Bridges freeze, factories overheat, and constant pressure strains joints. Phenol-formaldehyde resin stands up in these places because of its fire resistance and ability to shrug off all sorts of chemicals. Electrical switchgear, automotive brake linings, and circuit boards all rely on this feature. In electrical gear, insulation failure can lead to blackouts or fires. Here, the resin has been trusted for decades to resist breakdown where others fall apart.

People often think about plastics as something slick and bendable, but phenol-formaldehyde resin helped launch the age of molded engineering materials. In my experience, anyone who repairs old radios will know the classic “Bakelite” feel—a rich brown that smells faintly sweet when sanded. The early telephones, electrical plugs, and camera parts used this resin for its heat resistance. These molded objects last a long time and don’t melt or deform with regular use. Even today, brake pads, gears, and handles owe their solid feel to this development.

Factories often line their tanks and pipes with coatings derived from phenol-formaldehyde and similar resins. These are chosen for more than just low cost—they resist solvents, acids, and even the rough and tumble of constant cleaning. In print shops, some inks sit atop papers that have been treated with these coatings, helping books and packaging stay crisp instead of curling and cracking. Workers spraying or brushing on these finishes need proper protection, for sure, but in return, the equipment lasts longer and resists rot or rust.

Resins unlock plenty of benefits, but experience in woodworking shops and industrial labs makes it clear that health risks can’t be ignored. The formaldehyde released during production or cutting pressed boards has caught researchers’ attention for its role in eye, nose, and throat irritation, and some studies link long-term exposure to higher cancer risk. Factories now rely on tight air controls, better ventilation, and stricter formaldehyde content regulations to keep workers and customers safe. Consumers will see more low-emission labels on plywood and furniture—a push that helps everyone breathe easier without leaving behind these strong materials.

My first real encounter with phenol-formaldehyde came during a college project, where the assignment required making wood panels tough enough to withstand daily abuse in a communal dorm. The results stuck with me. Long after cheaper boards cracked and warped, those panels stayed strong and kept on doing their job. That experience taught me more than any textbook—the stuff works, and it lasts.

Walk through any hardware store and you’ll see engine parts, electrical switches, and handles made from phenol-formaldehyde resins. Take electrical switchgear—most folks hardly think about what keeps the lights on. This resin gives electrical parts that needed heat resistance to keep circuits safe. It’s the same story with car brake pads and under-the-hood components. Temperatures in those areas spike, and any ordinary plastic would melt or break down. This resin keeps shape and strength in those harsh spots.

Products see heavy use. Cabinets, floors, and wall panels catch scuffs, take hits, and face water spills. Phenol-formaldehyde-infused plywood stands up to bending and twisting in construction projects. Compared with regular adhesives, it creates stronger bonds that keep glued wood together even after years of humidity or changing seasons. Builders like this reliability, since it means fewer repairs and improved safety for families.

Everyone wants their home or workplace to feel safe. This resin doesn’t catch fire easily. That offers real peace of mind, whether installing electrical insulators or framing basement walls. Plus, bugs and mold don’t eat it. Wood products treated with phenol-formaldehyde fend off termite damage better than most untreated materials. This matters for both city high-rises and houses in damp, rural places.

Long-lasting products cut down on waste. Phenol-formaldehyde doesn’t get the same attention as new bio-based resins, yet it plays a role in lowering the need for frequent replacements. Builders and manufacturers can use smaller quantities of wood because the resulting boards don’t fall apart easily. In my own work, I’ve seen shipping crates and heavy-use workbenches last far longer when made from these resins, sometimes doubling their service years. That’s less wood heading to landfills.

Concerns remain around formaldehyde emissions. No one wants indoor air filled with harsh chemicals. Over the past decade, tighter regulations mean technicians keep emissions lower than ever before. Some new versions release almost no vapors after curing, giving everyone in the supply chain—from worker to homeowner—greater peace of mind. Still, using protective equipment and following best practices matters for anyone handling raw resins on the job floor.

Companies can continue refining their formulas, trading off small gains in cost for big improvements in indoor air quality. Projects can source panels that come certified for low emissions, like those stamped with CARB Phase 2 or similar programs in Europe and Asia. Factory staff involved in manufacturing need strong training and well-ventilated workspaces to keep risks low.

Real change often happens at the jobsite. Choosing phenol-formaldehyde makes sense in places where strength, reliability, and fire protection matter most. For jobs demanding lower emissions or frequent recutting, other modern resins may fit better. Each use has its place, but the benefits of phenol-formaldehyde products keep them a staple across construction, automotive, and electrical work—something I’ve seen and trusted throughout my own years on building crews and shop floors.

Anyone who has worked around phenol-formaldehyde doesn’t forget the sharp, choking odor. Phenol can burn skin in an instant, and eyes start to sting just from getting near. In my old lab job, I saw a technician rush to the emergency shower after a few careless seconds with a pipette. Quick responses matter, but a safer approach starts with avoiding exposure in the first place.

Gloves, goggles, and a lab coat are bare minimums. Hands soak in chemical residue through little cuts or even slight cracks in skin, so latex or nitrile gloves beat bare hands every time. Face shields give another layer for splash risk, especially when heating or pouring. Some people brush off the need for fitted respirators, but I’ve met colleagues who regret it—once you develop irritation or chronic cough, the regret stays.

Long sleeves and sturdy shoes finish the gear list. At the end of a shift, I learned to never carry traces home: a change of clothes in the locker, then a careful scrub before heading out.

Fume hoods aren’t just for dramatic effect. Their power lies in flushing toxic vapors away from lung level. In research facilities, I saw air quality monitors warn us before fumes hit dangerous limits—simple prevention, less cleanup. Every bench needs designated spill kits. I’ve reached for absorbent materials during a minor beaker accident; without the right kit, the risk can spread across the whole room in seconds.

Label everything clearly—phenol-formaldehyde won’t wait for a second guess. I saw one intern mix up containers, and it sent half a shelf of samples to the hazardous waste bin. Lock corrosives and toxins like these behind well-marked cabinets. Only open containers in areas with spill trays. If the bottles look older than your safety shoes, it’s probably time for disposal.

Instruction matters just as much as equipment. No one should touch phenol-formaldehyde without real training. Practical drills help. When I started, senior staff set up mock spills. Friends who passed the “watch a video and sign a form” kind of orientation had more small accidents.

Mistakes happen, but quick reaction keeps small incidents from pushing someone to the hospital. Washing off splashes, even minor ones, needs to be automatic. I keep emergency contacts and procedures taped to the storage door, close enough for anyone panicking in the moment. People who hesitate or don’t know the closest eyewash station become the most vulnerable to injury.

Mixing up a new batch or running old resin through a machine, maintenance schedules can’t be skipped. Corroded seals, failing ventilation, blocked exits—simple things turn deadly if ignored. Regular checks and honest oversight show up on safety records, and people stay healthier. Facilities that run real audits, with walk-throughs and follow-up—a lot fewer scares, a lot more confidence.

It’s simple discipline and clear habits that keep phenol-formaldehyde incidents rare. The goal isn’t to avoid all risk, but to respect the danger and trust your training. Getting careless isn’t worth a lifelong health problem from a single day on the job.

Phenol-formaldehyde resin made its debut over a century ago, grabbing headlines as the backbone of everything from pool balls to circuit boards. Old-timers remember Bakelite radios, and electricians still pull dusty, brown terminal blocks from boxes of leftovers. There’s a reason this plastic hasn’t faded out of the spotlight. Good resins stand up to harsh work, and this one keeps its reputation mostly because of its grit against heat and chemicals.

Turning up the heat—real manufacturing heat, up near 180°C or even higher—won’t phase phenol-formaldehyde resin. Thermoset plastics get their strength from tightly crosslinked chains, and this resin has plenty of those. It won’t flow or soften at temperatures that make most plastics puddle or deform. I saw this in the electronics shop: relay bases and switches made of brittle brown phenolic took years of arcing and buzzing without turning to mush. Components that handle heat day in and day out, like automotive distributor caps or circuit board substrates, trust this material to keep their shape and carry loads.

Factories and labs don’t just worry about things getting hot; they need materials that won’t rot away in the presence of harsh chemicals. This resin forms a structure that resists acids, oils, and alcohols. I worked with machinists who used phenolic jigs to measure out aggressive solvents—parts held up long after softer engineering thermoplastics failed. That toughness doesn’t cover everything; caustic alkalis chew through phenol-formaldehyde over time, and strong oxidizers will inflict damage faster than most users realize. In real-world settings, most users find resistance against daily chemical exposure far outpaces plastics like polystyrene or ABS.

A closer look at industries relying on stability shows this resin’s value. Electrical manufacturing turns to phenolic laminates for insulation—a broken-down insulator can mean the difference between working machinery and ruined equipment. Appliance handles and gears keep moving without melting, even when ovens run non-stop. In my own experience, garage tools with phenolic grips don’t turn sticky or brittle the way cheaper plastics do after years of oil and sunlight.

The flip side: shaping phenol-formaldehyde resin brings headaches. Unlike thermoplastics, it can’t be softened and reshaped with heat once it sets. Production molds must be accurate the first time. Once cured, repairs get tricky, often forcing replacement of entire assemblies instead of patching broken bits. Environmental problems stack up, too. This resin isn’t bio-based, and leftover formaldehyde fumes during shaping spark safety concerns that makers must address with ventilation and protective measures. Years back, I watched workers carve phenolic panels behind fume hoods for good reason.

Engineers and suppliers double down on training to handle phenolic materials correctly—good safety practices drop workplace illness. I’ve seen some companies move towards recycling ground-up waste as filler in new composites, trying to keep costs low and leftovers out of landfills. Regulators recommend lower-emission formulas, and resin makers chase lower toxicity blends. Teams that pay attention to resin sources and follow strict off-gassing standards keep people safer and products trusted for daily use.

This resin’s tough, and time keeps proving it in real applications. People who work with phenol-formaldehyde stick with it for a reason, even while keeping an eye on safer recipes and improving cleanup. Its history and track record show that tough jobs often need tough materials—especially those that won’t quit under pressure.

Phenol-formaldehyde resin started shaping lives over a century ago. People know it best as Bakelite—think old rotary phones or the handles on grandma’s kitchenware. Behind these tough and heatproof products sits a chemistry lesson grounded in day-to-day utility: react phenol with formaldehyde, use simple acids or bases as a catalyst, and the result is a resin that stands up to just about anything heat or harsh cleaning throws at it.

Laying out the process isn’t about showing off technical terms but about real challenges faced inside a resin factory. Take phenol—clear and faintly sweet in smell—mix it up with clear, sharp-smelling formaldehyde. Toss in an acid like hydrochloric or a base like sodium hydroxide, and set things in motion. With acid, the chain grows shorter—good for adhesives and coatings. With base, longer chains create the rock-solid plastics of electrical components.

Temperature and timing matter a lot. My experience touring a plywood manufacturing plant taught me how rushed mixing leaves brittle resin, short on the bonding power needed to hold wood sheets together under pressure. Longer, gentler heating lets the chemical chains grow, and gives plywood its famous strength—a trick that’s helped the building industry boom.

Manufacturing isn’t a magic trick. Resin-makers face real headaches: formaldehyde fumes draw heavy regulation for their sharpness and health risks. Plant workers must gear up—masks, gloves, and strict ventilation. Once, chatting with a foreman, I learned how even a brief lapse in safety leaves workers with burning eyes and headaches; industry leaders push for closed-system reactors, cutting exposure and keeping both workers and neighbors a little safer.

Wastewater from these processes carries leftover chemicals. Dumping it untreated spells trouble for rivers and farms downstream. I remember a local news story where fish disappeared after a spill—residents pressed for tougher cleanup rules. Companies now lean harder on neutralization tanks and biofilters, giving pollutants a last stop before water heads back into the environment.

Supply chains affect even the chemistry behind these plastics. Price swings for phenol push managers to scramble for alternative sources or tweak their process to stretch each barrel. High formaldehyde costs can eat into the affordability of construction materials, raising home prices. My neighbor ran a lumberyard—each time chemical costs ticked up, customers grumbled at rising plywood prices, not realizing the story stretched all the way back to those raw chemical barrels.

Tough regulations help, but constant improvement in scrubber technology and closed-loop water use promise a cleaner tomorrow. Some labs work on bio-based alternatives, aiming for plant sugars instead of petroleum to feed the chemical reaction. Imagine plywood held together with resins made from corn stalks, leaving the air a little cleaner. As these tweaks roll out, communities will see safer jobs, cleaner air and water, and affordable materials for everyday life.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | poly(oxy(methylene-1,4-phenylene)) |

| Other names |

Phenolic resins Bakelite PF resin |

| Pronunciation | /fɪˌnoʊl fɔːrˈmældɪˌhaɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 9003-35-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1735242 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:53212 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1909077 |

| ChemSpider | 17736195 |

| DrugBank | DB11343 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 200-817-4 |

| EC Number | 232-523-7 |

| Gmelin Reference | 971 |

| KEGG | C01676 |

| MeSH | D002829 |

| PubChem CID | 7257 |

| RTECS number | SJ3325000 |

| UNII | F9HGH62V5N |

| UN number | UN2212 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | (C6H6O)n·(CH2O)n |

| Molar mass | Molar mass: Variable (depends on polymerization degree) |

| Appearance | dark-colored, solid or resinous mass |

| Odor | Distinctly phenolic |

| Density | 1.18–1.20 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | slightly soluble |

| log P | -0.31 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.1 mmHg @ 20°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa ≈ 10 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.2 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.673 |

| Viscosity | 30-60 cP |

| Dipole moment | 1.7 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 117.8 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -92.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3221 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | D08AX13 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Toxic by inhalation, in contact with skin and if swallowed; causes severe burns; may cause allergic skin reaction; suspected carcinogen. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS06, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS02,GHS05,GHS06 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H301, H311, H331, H341, H351, H372, H314 |

| Precautionary statements | P280, P305+P351+P338, P310, P261, P303+P361+P353 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 3-2-2-W |

| Flash point | 79°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 715 °F (379 °C) |

| Explosive limits | 1.8–8.6% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LDLo oral human 140 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 300 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | NIOSH: SJ3325000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5 ppm |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.1 mg/m3 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Phenol-Formaldehyde: IDLH = 250 ppm |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Bisphenol A Cresol Novolac Resorcinol Urea-formaldehyde resin |